Hermits, introverts, cat people, misfits, loners. Maybe more than any other profession or calling, writing suffers from centuries of received ideas that portray writers as people who like to observe, think, and isolate themselves to practice their craft. But that’s not how interesting, enjoyable, meaningful writing is done. Writers like me and my peers are endlessly passionate and curious about life’s questions and discoveries. In project after project, they connect with people, engage with issues, and take creative risks. By easing some of their more mundane workloads, AI support can help them develop productive relationships and tell unique stories. It needs to be used in a responsible, controlled manner so it doesn’t turn into a distraction.

Below, we consider common misconceptions about writing and highlight how a seasoned writer assisted by AI can help your idea, business, or mission succeed. For AI to be effective in this context, it needs to be in the control of an expert who understands content strategy and development.

The critical error in understanding writing

When it comes to writing, we’re operating under a kind of metonymy: we confuse a late, supporting part of the process with the interactive, creative, sparkly event that writing is at its best.

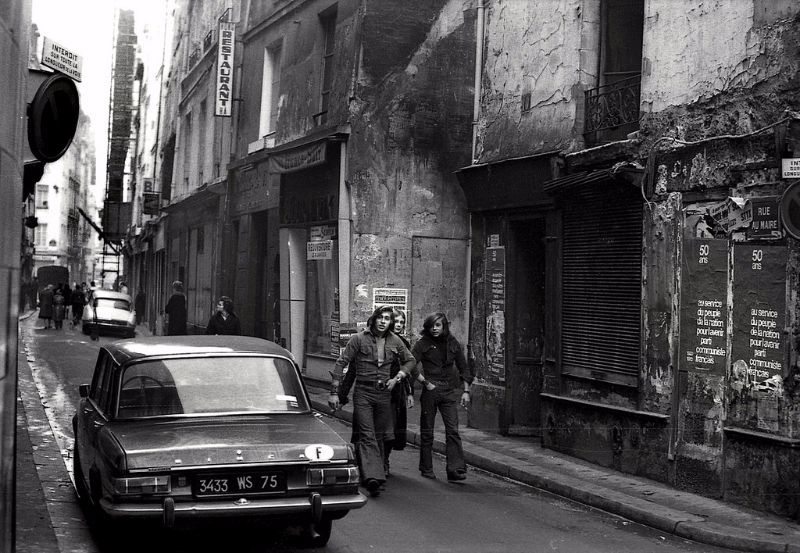

What do we typically imagine when we think of writers? For eons, they have been depicted as people who sit, stand, or crouch at a workspace, like a table or a cave wall. They often hold objects — chisels, hammers, quills, keyboards, pens, brushes, spray cans. By means of these tools, they cause hieroglyphs, letters, numbers, pictographs, ideograms, and symbols to appear on various surfaces, including moist clay, screens, paper, stone, parchment, tree bark, slate, and others. In this way, writers express ideas, relay information, tell stories, make recommendations, issue promises, and so forth — they commit a broad variety of speech acts. When people perform according to this traditional model of writing, we may find them in a chamber, surrounded by shelves and stacks of books, scrolls, or clay tablets; hunched over a laptop while occupying a table with four chairs in a coffee shop; or even in a kind of cell, like you find in convents and cubicle-based environments.

We should recast our view of what writing is, because these conventional representations have little to do with the dynamic, high-energy reality of writers and writing. Of course, you might observe writers handling traditional tools in the quiet, harmonious, clean, and well-lit locations. However, at that point they are already close to done. Late in their process, they create a record of their ideas, questions, inventions, or findings. We are used to thinking of this obvious and visible stage of the work as the entire undertaking. That is understandable, because writing can be such a many-faceted, fast-paced activity, but it’s really a gross simplification.

How does writing happen, then?

Most actual writing takes place in moments when writers are fully awake and engaged with the world. It’s not a private, genteel pursuit, perfect for those who like to keep a distance from the chaos and beauty of everyday life. For example, many writers thrive on encountering and talking with people. They love asking open-ended, engaging questions of interviewees and subject matter experts, and listen with complete attention to the responses. In these conversations, they may hear something fascinating which they didn’t expect, and they know how to pivot instantly and explore a possibly important idea.

Good writers are empathetic — they can make people feel appreciated, safe, and comfortable. They instill in their conversation partners the confidence that whatever they share will be cherished, treated appropriately, and make a difference. At the same time, they keep exchanges on track, so they remain lively and enjoyable, and don’t degrade into small talk or dead ends. If they have a tentative narrative strategy before they conduct any interviews, they amend and update it in light of what they learn.

When writers conduct research, they remain as open-minded as they do in their conversations. They have the insight to revise their lines of inquiry to be unrestrictive and largely free from bias. They know how to find documents and resources of high promise and how to spot voices and materials that are overexposed, simplistic, or misguided. They understand their own limitations when it comes to understanding and representing complex ideas, events, and processes, and can check their tendencies to misinterpret, overlook, or confuse them. Their curiosity, judgment, and experience help them do justice to the issues, people, and organizations featured in their writing.

Creative intelligence without boundaries

In support of your mission or business, experienced writers can apply their creativity, developing a unique voice and tone to tell stories or help people make sense of questions of the day, innovative trends, social and technological changes, historical milestones, and lots more. They can shape and deliver a message in such a way that readers find it relevant, memorable, unique, and attractive. It takes writers years of growing their skills to do this well. But it’s worth it: your trusted writer can provide you with a set of extra wings in a way nobody and nothing else can.

Like other creative activities, writing has its own uncompromising pace and intensity. Once writers engage with a client, an issue, or a project, their minds keep working as they think, process, and play with concepts and phrases even when they are still interviewing people or conducting research. Many writers are like magpies, always on the take, listening and paying attention to how people assert, describe, promote, and question things. They pick up emerging nuances in commonly used words and unearth surprising and illuminating ways of expressing things. They ride the bus, walk the dog, or go grocery shopping and come home with little revelations about what they can do with words and ideas.

AI can assist writers in working to their strengths

Having heard the standard tales about how AI can doom creativity or drive remarkable transformations, you might be wondering whether generative AI can truly write well. Given the right prompts, can it be successful in taking on writing tasks? Can AI simplify the writing process and remove some of the busywork from it? The answer is yes, in the hands of a writer.

For example, AI can help writers identify and extract useful material from various sources, research issues, summarize documents and websites, calculate values, experiment with ways to articulate ideas, and come up with fresh outlines. One needs to test and verify what AI offers, but it can be invaluable. It can give writers time back for more exciting work where humans excel — talking to and learning from people, exploring diverse ideas and voices, and creating fascinating, relevant content that doesn’t capitulate to common routines.

When AI practitioners become more savvy, they can put AI to work at a more advanced level. It can quickly and accurately recast messaging frameworks and other source documents in different formats; patiently conduct simple, routine interviews; and deliver workable drafts of plain documents like features lists or technical specifications that need minimal treatment before publication. Again, you need to validate what it delivers so it’s free from errors, redundancies, and misjudgments.

AI allows great economy in a tree-like content model

In your content program, you can rely on AI for the supporting tasks that suit it and work with seasoned writers on projects and long-form documents where their creativity and insight can make a difference in quality and impact. For instance, you should leave your in-depth interviews, with all the diplomacy, empathy, and flexibility they may require, to experienced human writers. Especially in longer documents, AI writing can be repetitive and monotonous, whereas a skillful writer can keep readers engaged with clear, sparkly language that avoids clichés and overused notions.

You can think of your foundational, longer-form content as the trunk of a tree that can generate many different branches. Once a creative writer has completed and polished a longer, original document, you can task AI with using it as a source for the first drafts of social media posts, video scripts, and other derivative pieces. These still need to be reviewed carefully, or mistakes, repetitions, and flat passages may ruin them. However, generative AI can faithfully translate source content into other vehicles without adding phrases and nuances that deviate from your message, which is always a possibility with human operators. In this case, the mimetic quality of AI, which has to draw on established, already articulated ideas and published documents, can clearly work to your advantage. Using it that way can help you control costs and get simpler writing assignments completed quickly.

Freedom from the herd: content strategy with AI support

AI operates within a confined realm, depending on your prompts. For example, it could help you create a content strategy and define the content vehicles and formats, but in doing so it will consider any existing strategies and tactics it may locate. You can use AI findings to learn how other people and companies tell their stories and engage with target audiences, but adopting their practices will make you look like an also-ran, not a leader in your field. Companies’ imitating and cribbing from each others’ content and ideas is already a problem that frustrates readers aiming to educate themselves and make the right decisions. When too many organizations and their products and services sound alike, the risk is high that you might choose a limited, imitative provider with poor viability.

Carelessly applied AI will only make conceptual plagiarism and generic content writing worse. The ease‑of‑use and speed of AI tools may tempt more marketing and communications managers to take an easy, low-budget route and create what amounts to placeholder content instead of telling a unique story. A resourceful writer who is also an expert content strategist, on the other hand, will consider what AI offers, adapt and turn it around, and build a unique content strategy that fits your identity, values, and goals. By relying on AI to do much of the preliminary groundwork of research and industry assessment, you can get to a practical, distinctive content strategy sooner than you might otherwise.

A strategically smart writer can also advise you on the impact of narrative approaches and word choices with readers and decision-makers. When hundreds or thousands of sources of content and ideas compete for a share of their attention all day long, a writing partner steeped in the trends and possibilities of language and storytelling help you stand out.

Contact me at chrislemoine[at]fastmail.com to explore working together or have your writing and content strategy questions answered.